A short review by Lusi Lukova

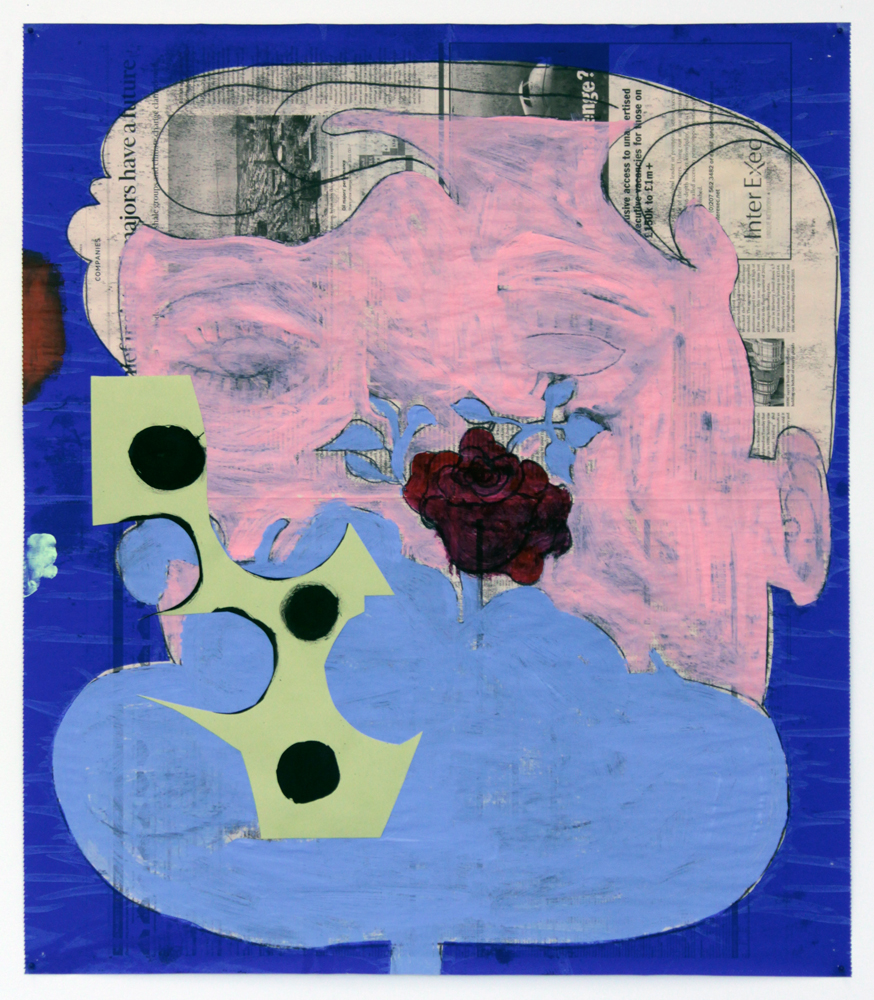

Cocoon Dance, 2019, acrylic ink and paint on satin, 27 x 28 inches

With her debut solo show Pansy at Nationale, painter and installation artist Michelle Blade melds iconic imagery and unruly mediums to demonstrate the unpredictability of painting. Pulling from the biblical narrative of Adam and Eve in the Garden, Blade focuses her artistic energies on Eve, and other feminine mediations of her spirit in these new works. In an attempt to explore the feminine relationship to the land, to knowledge, and to a sense of community, these pieces evoke an almost illustrative and magical quality. Each of these paintings depict large-scale scenes of the garden and the earth in dreamy shades of pinks, blues, and yellows. In the traditional narrative, Eve is scorned for her defiance. However, in Pansy, the expectations are reversed and the unforeseen beauty and strength of the feminine are revered. Just as humans are unpredictable and far from foolproof, in each of these paintings Blade explores a personal coming to terms with how perhaps it was a woman’s doing that set the path forward to everything else but perfection. As a result, Blade navigates our attention to the particular synchronicity humans share in the creation of everything in our immediate and tangible worlds.

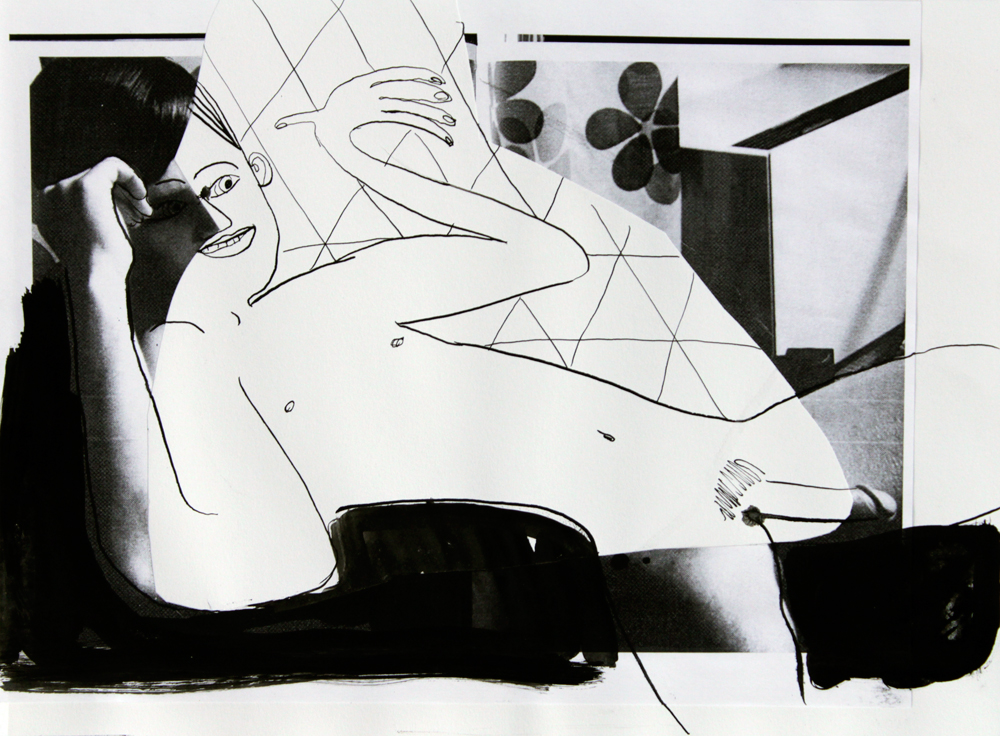

Tree of Knowledge, 2019, acrylic ink and paint on satin, 31 x 27.25

The works presented are all painted on satin, a new format of expression both for Blade and for this historical imagery. The artist deems the material “alive” in that it shifts with each stroke of the brush. Unruly and independent, much like Eve herself, the satin allows the paint to bleed in unprecedented ways, the acrylic ink becoming so fluid that it resembles watercolors over anything else. Due to its sheer nature, it also allows for light to leak through in a similar fashion, adding an ethereal, almost divine luminosity to the works. In the bleeding of the ink, there form abstractions which we can liken to a physical representation of the mysteries of the universe. Presented as meditations on beauty and the natural world, works like Pansies, in which a woman is communing with a snake, are overt in their symbolism while coyly presenting a duality of the female. She may give in to speaking with the snake, but she is also fearless for doing so. As a whole, this exhibition questions these historically gendered tropes and ultimately comes to the conclusion that perfection is not to be neither expected, nor exalted.

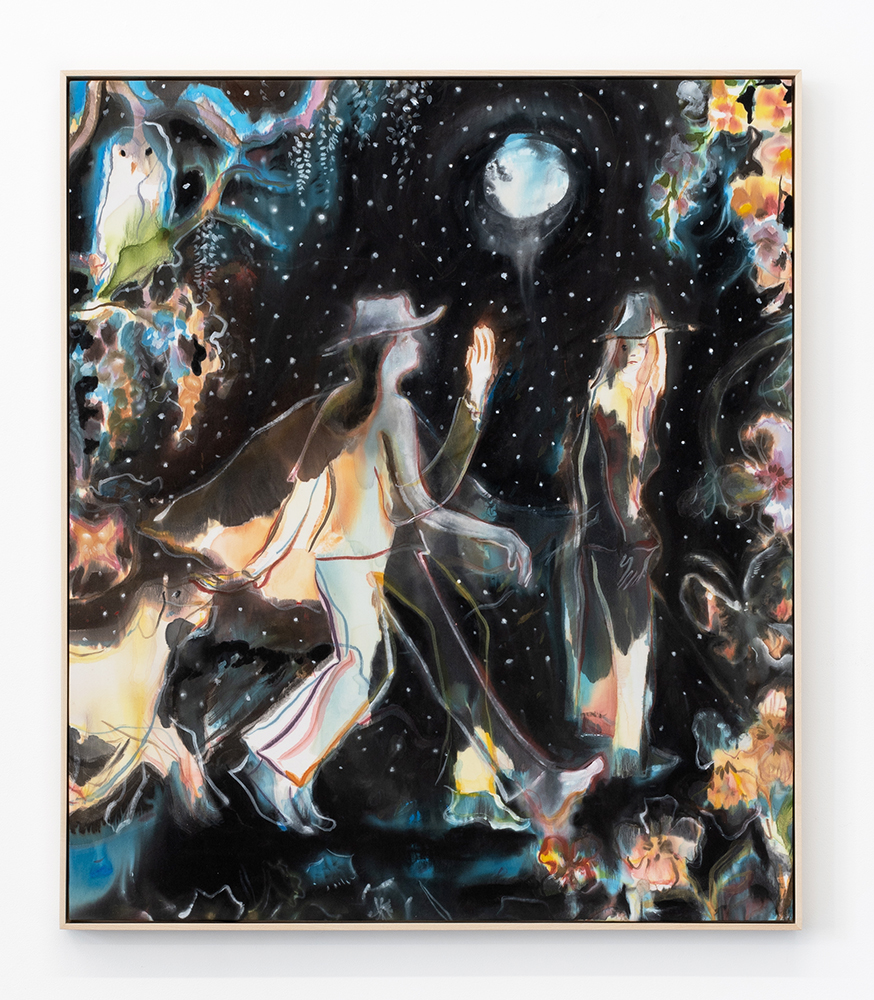

Moon Twin, 2019, acrylic ink and paint on satin, 42.5 x 27 inches

Michelle Blade’s Pansy is on view through June 4th, with a print release and closing reception on June 2nd, from 12-2pm.