GLL: You often draw imagery from your childhood growing up in Spokane, WA. How has it influenced this series?

TE: Spokane is a merit badge I wear. The heron, the cowboy, the buck skinner, the fast food rabbit, they are all icons from my own personal experience. My own upbringing. In talking about Sam Sheepdog and my day job where I put on this act of portraying my work-self, what comes with that is also this realization while working with large groups of people that I don’t have many common interests with my co-workers, we don’t recall the same things from our youth from living on the same earth for roughly the same amount of years. I’ve seen so many instances where two, three, four, five people just mesh. You set them at a table and they have these long conversations where their recollections from childhood are almost synchronized. I’ve come to realize that with my co-workers I like some of the same music, but I can never remember the movies from the 80’s and 90’s that are quoted, I can’t join in on the Star Wars conversations that happen, far too often by the way, and I can’t relate with most people’s travel stories. My childhood was spent in Spokane and inside my own head, daydreaming, wandering. I had interests of course, I skateboarded and played baseball and ice hockey, I read, listened to music, I watched movies, but I didn’t retain much from any of these things. I could write a novel about listening to Pearl Jam Ten in sixth grade or Wu-Tang in the eighth and all of the places in which I listened to them, but I can’t recite more than three or four lines from either, and I listened to them a lot. A lot. And Wu-Tang I still do. Same goes for Elliott Smith and his albums later on into college. From all of these experiences, what I have retained are the experiences themselves. Little vignettes where the music served as a soundtrack. That doesn’t translate into a universal conversation that you can bring to a table, it’s way too personal. This has isolated me. It has made me unique, I suppose, but ultimately, lonely. Spokane was my WORLD. I can’t help but return to it when I sit down and try to process things or express myself. It’s the stage everything played out on for me. I know myself. I know Spokane. I don’t know much else. I think a person’s place of upbringing is monumentally important. I recently read that Ingmar Bergman once stated that regardless of where he was born and raised he would still be the Ingmar Bergman we know. That’s bullshit.

GLL: Much of this work and your past work, is deeply personal and seems to grapple with ideas and perhaps misconceptions on what it means to be a MAN. How does masculinity and the struggle for finding that identity play into this work?

TE: It’s a tough subject for me to talk about. That’s probably why it comes up in my work so often. My work is where my most intimate and personal conversations take place and they’re still encrypted. I’m 35 years old and I’m still learning how to speak. I read a lot, I surround myself with our language, I try to immerse myself in it so that I can express myself clearly and eloquently. I want to SPEAK. But, I just trip on my tongue. I think I grew up with a learning disability that I was completely unaware of. I don’t have a clear and tight grasp on things. So much of being a MAN is being able to communicate clearly, stand up for yourself, set good examples, and be strong in the process. To inspire. Then there’s this other aspect where you have to be physically strong and good with your hands and not make mistakes. You have to be witty and on point. A good MAN can’t ask questions. He has to know the answers. He’s gotta be in tune with nature and know how to tie all of the knots. Set up a camp. Dig himself out of snowdrift. Swim himself to safety. He has to be good with power tools and automotive shit. He has to protect himself and his family and not show sweat. He’s gotta be prepared for the big one. He has to fend off intruders. The list goes on and on and on. And each of these things has to be handled with the utmost confidence. My understanding, is that in our society, if you’re not into certain things and don’t know certain things, then you’re not a man, and I’m left feeling unmanly all of the time. My masculinity is challenged daily. I’m still getting bullied at 35 on a regular basis. My work is from the perspective of the flashlight holder.

GLL: I think that comes through because along with that idea of masculinity there is also a softness, a tenderness and even a sense of humor to this series that seems to counter that need to be a “tough guy.” It also feels personal and universal at the same time.

TE: We need to laugh more. We need to laugh at the “tough guy” more. Fuck the tough guys. It has gone too far, they’ve had their turn. My daughter lately has been telling me, “Be happy, Papa!” I have no idea where she got this, but seriously, happiness needs to be the universal theme. It’s got to be.

GLL: There are big vinyl letters on the wall that say your name and then “Stupid Man” below. Can you talk about the title Stupid Man? Is it meant to be self-deprecating?

TE: Yes and no. I have low self esteem, I’m insecure, I suffer from social anxiety, I grew up wetting my bed and sucking my thumb. I was called a pussy and a fag a lot as a child and even when I first moved here to Portland in ’99 I had people yell, “fags” at my roommate and I from their car window as we walked down the street. I’ve never felt masculine or manly in the slightest. I have always been afraid of men and feel that my work comes from my feminine side. I guess none of this has to do with being “stupid,” but it has to do with being misunderstood and judged. I mentioned earlier that I often trip over my tongue. I am not comfortable with the words that come out of my mouth a lot of times. I feel I poorly represent myself with my speech. I don’t have a large vocabulary and my dictionary app is my best friend. You would be surprised by some of the words I’ve looked up over the last six months. I know that I am not, but I often feel stupid. My geography, world history, and politics are bad, I am working on these things now at 35, because none of it stuck in my teens. I feel behind. In addition to all of this, my heroes are intellectual, activist types. The ones that stand up for themselves, liberate themselves. Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, who both appear in this show for example. They embrace their femininity and give the middle finger to the Man’s man. Last summer, when I had finally figured out where this show was going and what themes I was working with, when I was actually able to envision how this work might appear, May and I were at our friends’ house for dinner and The Bells came on. It begins with the track Stupid Man. A beautiful song about a deadbeat dad that only Lou Reed could write. I remember as it came on telling May that my show was going to be titled Stupid Man, and we just laughed.

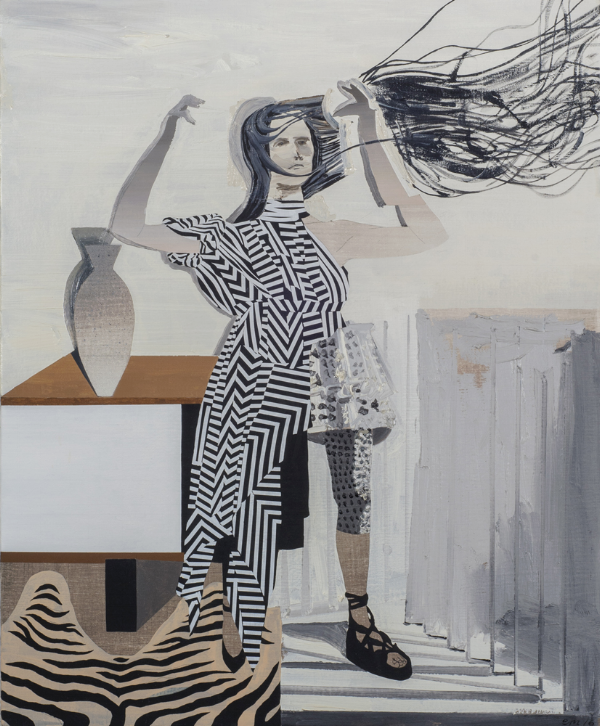

GLL: You showed two studies or “failed” paintings during our group studies show in February. One was of a woman (though the canvas was sliced down the middle) in a long dress and heels. After thinking about that piece I realized that there are no images of women in the final show. Was that a conscious decision to remove the female subjects to focus on notions of masculinity?