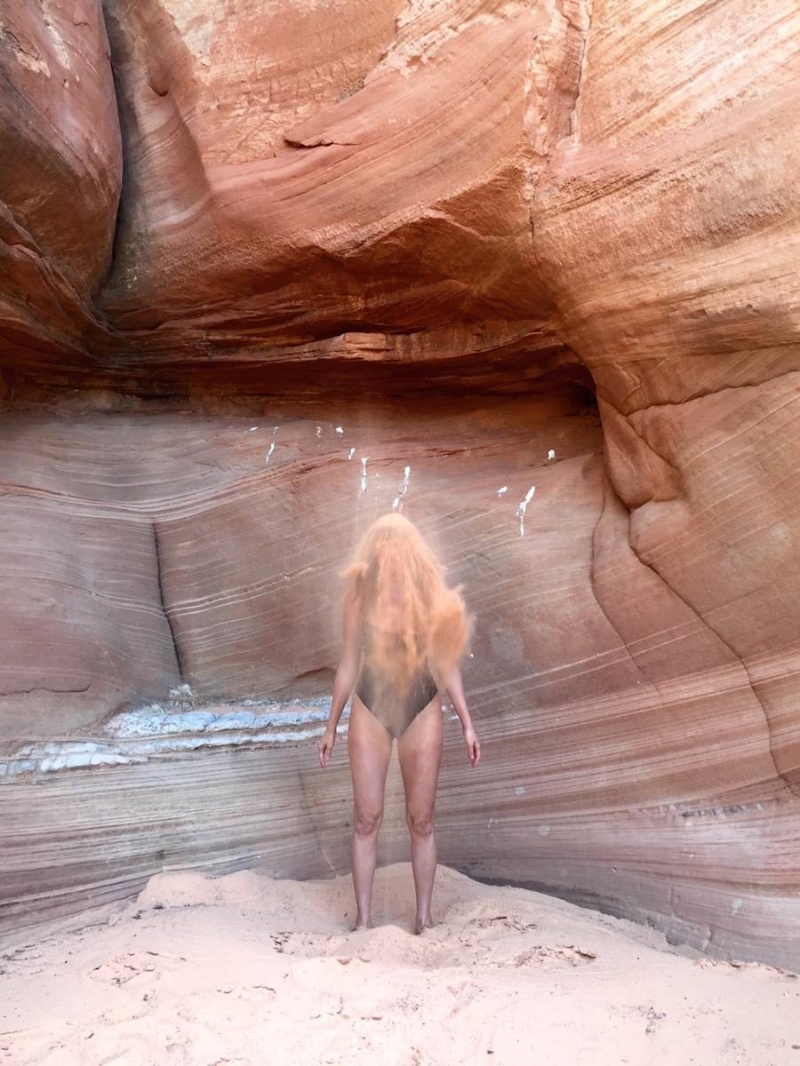

GLL: Amy, we spoke before about how you often work on the ground to get rid of the hierarchy of shapes and spaces. So, speaking of abstraction, my question is, how is orientation important to you in the final work?

AB: I do work a lot on the ground because I don’t want the work to be affected by gravity. But, I think somehow these works still got a little affected.

PK: What exactly do you mean by being affected by gravity?

AB: Every time I work in a way that I exist in my body, with my feet on the floor and the work on the wall, I eventually start making the world around me. Things start to move to the bottom of the picture plane and all of a sudden, it’s like the real world, and that’s not what I want at all in this work. So, I have to work on the floor because gravity always seeps in. I don’t want to make the physical world in my painting, so I have to work on the floor.

GLL: So, you don’t want that horizon line...

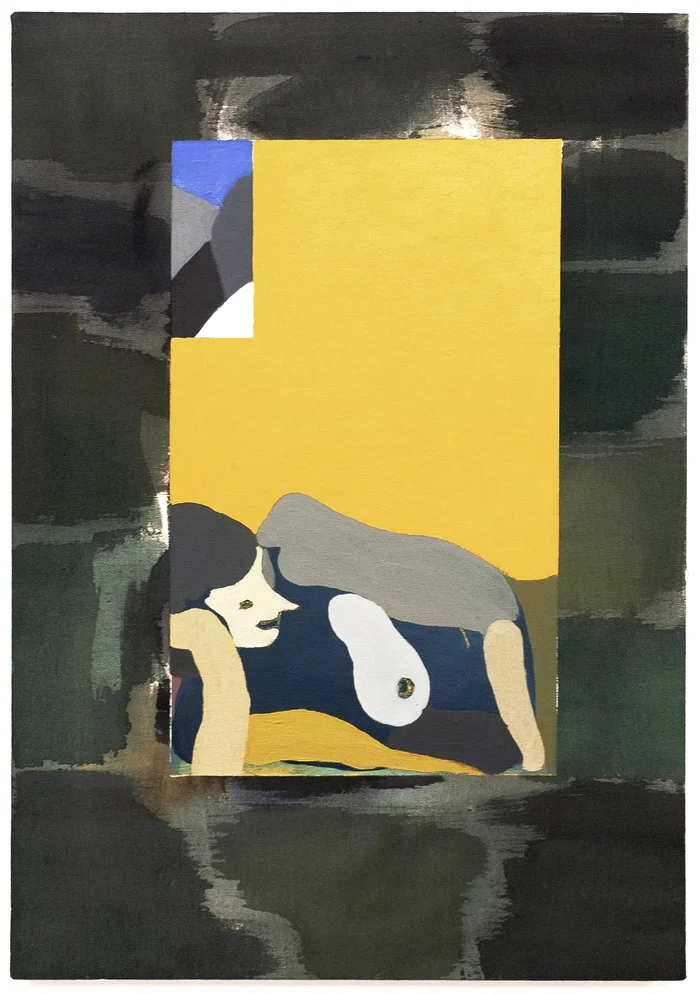

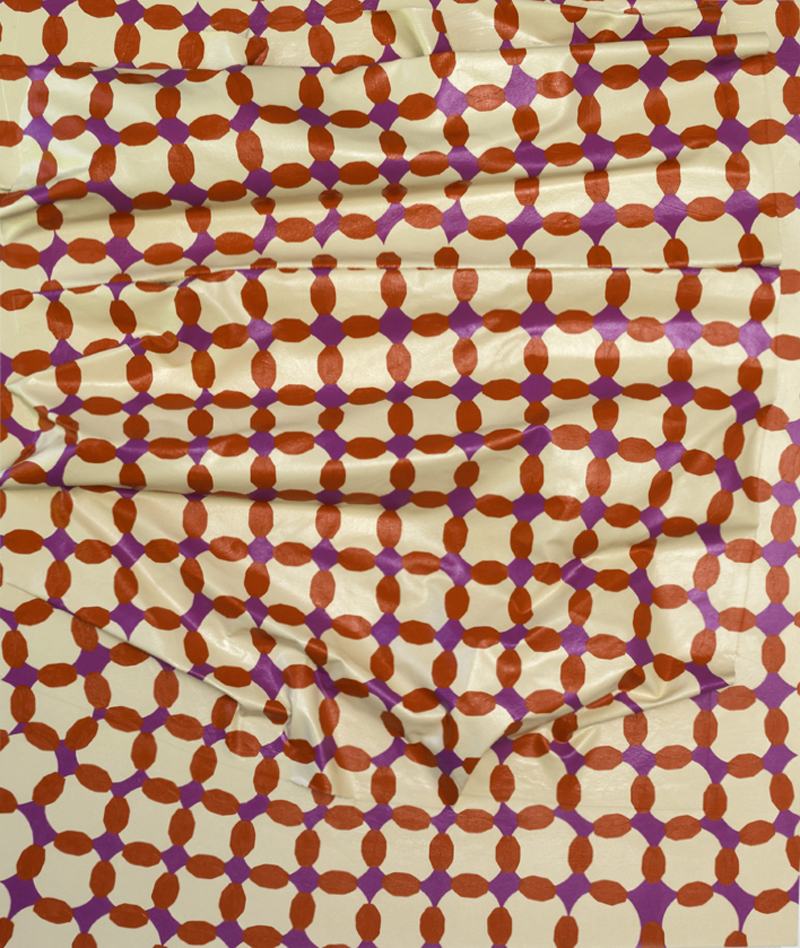

AB: Exactly, well, not really a horizon line, but the way things are weighted, a top and a bottom, a right and wrong, an up and down. Even when I look at the work and make a decision while the work is on the wall, gravity happens again and confounds me. I don’t want my characters to be affected by those rules. Gravity is so inescapable, it turns out!

PK: It probably is like one of the most inescapable things!

AB: But you’d think in my painting it doesn’t have to exist, but it does, it gets in there. I have had people turn my paintings different ways. I think of them as being oriented a certain way, because for me they do something for me that way. I want to not care if it’s oriented in a different way, but I probably do.

PK: Yea, you probably do.

AB: Yea, I do. I read this wonderful idea that I want to take on as my own but I can’t because I’m just not being honest. You know there was that awesome aboriginal show over the summer (No Boundaries: Aboriginal Australian Contemporary Abstract Painting, presented by PICA) and those artists were like, “put this piece on the floor,” because the way that they orient space is just so fantastic, and they don’t cater or work in any of our western pictorial constructs of making a landscape to explain your experience at all, which I thought was the most fantastic thing in the world and which I wanted to do so badly. But honestly, I know someone who owns one of my paintings and has turned it a different way and every time I walk in the room I’m like “ehhh...that’s not right.” But, you put it in the world and it’s not yours anymore.

GLL: And Patrick, with your work you are definitely working on the wall.

PK: I am, yea.

GLL: Physically, it would probably be difficult to work on the floor.

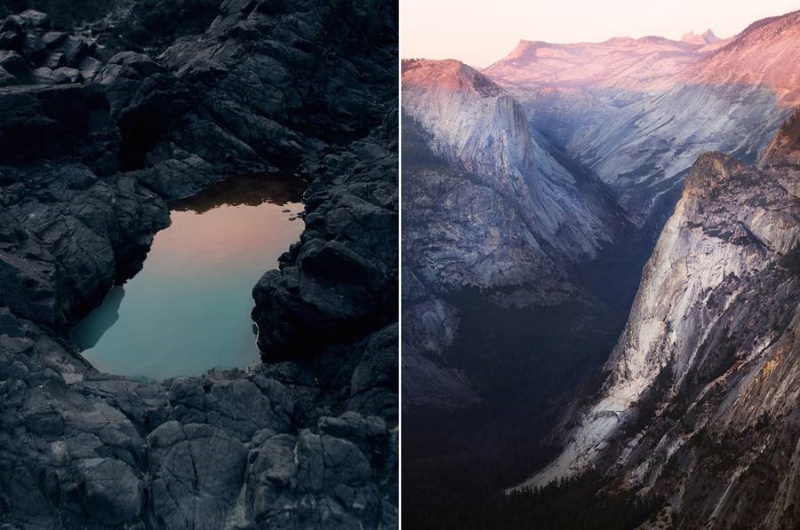

PK: It kind of would be, but honestly when I’m making these too, I am kind of twisting and bending so many different directions. It’s really kind of strange. Sometimes if I find my body in a stressful situation all of a sudden, I’ll switch to the other side and find another position. Once a work is completed, I’ve always enjoyed the fact that there is not one fixed spot in which to view it, for the fact that under certain amounts of natural light affecting it’s constantly changing.

GLL: Which brings us back to the idea of time.

PK: Right.

GLL: But in terms of orientation, you know from the beginning how a piece will be placed on the wall?

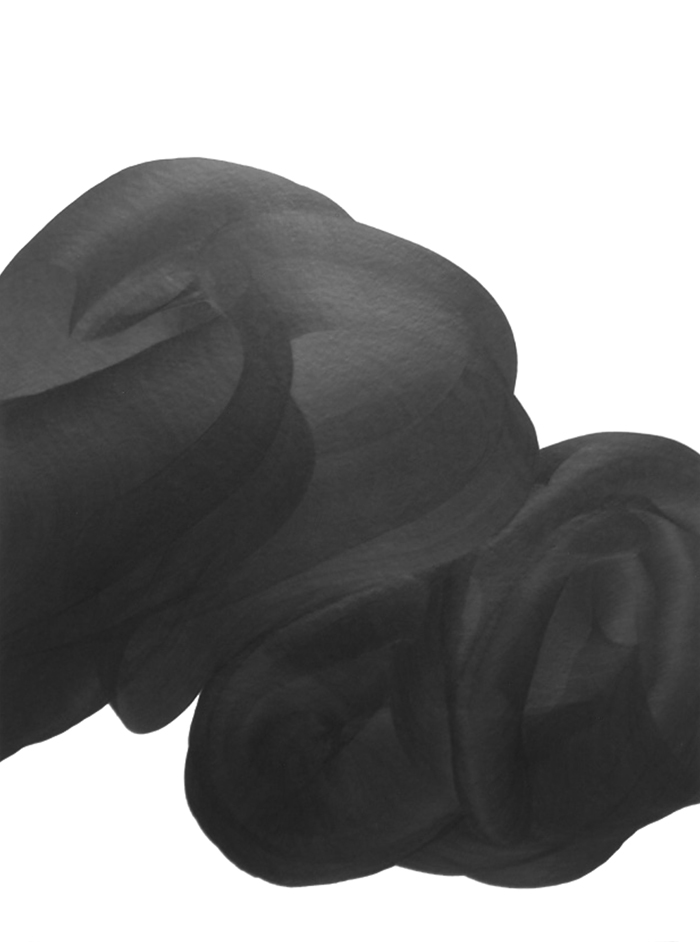

PK: Yea, I don’t ever really turn the page when I’m working. I haven’t really gotten to that point because I don’t know the reason why to do that, other than just to do that. Usually, I orient a page and say this is how I’m going to work, in this format. It’s interesting when Amy was talking about trying to rid yourself of gravity, because I’ve really tried to do that as far as keeping these images floating in space to almost feel weightless, outside of the fact that they also feel very heavy, very dense.

GLL: And these newer pieces on black paper, almost feel like a piece of a larger one or a zooming in.

PK: Yes, somewhat, getting a little bit closer in. Maybe a little more terrestrial. The black paper was really started as more of a curious thing of seeing what could happen.